This is a set of game design lessons covering theory and concept tools. It’s intended to expand on the Game Kit’s topics, but on a different scope. We are not yet sure for how long will it run, or what topics will it cover: we need you for that! Go ahead and leave feedback through any mean you fancy. We want to know if you liked it, and what would you like to see next!

The notion of Flow was created by a wacky psychologist named Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi (apparently pronounced “chicks send me high”… go figure!) in the 60’s. The study on flow came into being when Mihaly started questioning why some people get so focused on the task they are doing that they lose sense of their surroundings and their own self. They forget to care for bodily needs, and for a brief lapse of time there’s nothing else in the world except the activity they are doing. I think that understanding the link between Csíkszentmihályi’s work and our own work as game designers plays a major role on shipping great games. This post aims at exploring that link, understanding the kind of involvement we want from our players. So, on with it!

Starting with a definition is a great kick-starter, so here we go: Thank you Wikipedia!

“According to Csíkszentmihályi, flow is completely focused motivation. It is a single-minded immersion and represents perhaps the ultimate in harnessing the emotions in the service of performing and learning. In flow, the emotions are not just contained and channeled, but positive, energized, and aligned with the task at hand. To be caught in the ennui of depression or the agitation of anxiety is to be barred from flow. The hallmark of flow is a feeling of spontaneous joy, even rapture, while performing a task although flow is also described (below) as a deep focus on nothing but the activity – not even oneself or one’s emotions”

From its beginning, the idea of flow was applied in several fields: art creation, music, business, programming and education, among others. Eventually, it was exported to game and video game design. Jenova Chen, creator of the game Flow, wrote his MFA thesis about how to implement the flow concept in video game design. But before we get into that, let’s take a closer look at what Flow represents for us as game designers:

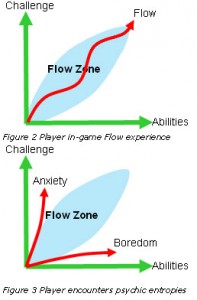

“In order to maintain a person’s Flow experience, the activity needs to reach a balance between the challenges of the activity and the abilities of the participant. If the challenge is higher than the ability, the activity becomes overwhelming and generates anxiety. If the challenge is lower than the ability, it provokes boredom. Fortunately, human beings have tolerance, there is a fuzzy safe zone where the activity is not too challenging or too boring, and psychic entropies like anxiety and boredom would not occur.” [Csikszentmihalyi 1990]

We are getting closer to seeing the value that Mihaly’s idea brings to game design. First of all, we now have the name of our enemies: anxiety and boredom. If your player falls prey to one of them (apparently he can’t be both) he’ll eventually abandon your game (probably depending on how resilient to those states he is). The magic word here is “challenge”: the challenge should not be too much or too little. It needs to be (to feel) just right So, it becomes clear what is it that you need to avoid. Now, how on earth are you going to do that? Well, Jenova Chen has been thinking a bit about it, and he has an idea or two.

Building Flow into games, the automatic way

Jenova’s thesis is all about implementing game mechanics that could provide a permanent state of flow to the players, regardless of their skills. If you have the time, go ahead and give it a read: it’s not that long, and it’s also a valuable game design lesson on its own!

The key point of the thesis has to do with Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment. The idea behind DDA is that the game should adapt to the player, in such a way that it constantly provides a challenge that’s right for whoever’s playing your game. It might sound good in theory, but trust me, this is an implementation nightmare! When considering the possibilities, Chen realizes there are two ways of implementing DDA into a game: the designer can either go for a Passive, unknown to the user mechanism that automagically sets the difficulty, or he can get constant feedback from the player to see if he’s having a good time. If he is, continue as is. If the game’s too easy, increase difficulty. You get the picture. This is, of course, riddled with shortcomings: a passive approach would need very well defined “enjoyment indicators”, that the designer is unlikely to be able to gather in game without a Mind-Reading Medium(tm) (crystall ball sold separately). Number of enemies killed, coins collected or jumps made are hardly things we could use to adjust the difficulty settings. On the other hand, having a popup window constantly asking “Are you enjoying yourself? Yes/No” is, at least, weird. And it doesn’t guarantee we get the information we need, because what exactly does he mean when he says yes or no? Maybe he just likes the pretty graphics…

So, is a player-oriented DDA suitable for everyone? No, it probably isn’t. Actually, I’d say it’s downright impossible: to me, Jenova Chen’s pursuit of a perfectly balanced flow machine that would take all gamers, regardless of their background, into a zombie-like state with no self-conscience is an impossible dream. And still there’s much to learn from this, about flow, and about how the players enjoy the games we create. Regardless of the fact that Jenova Chen’s game, Flow, isn’t a perfect translation of his theory into practice, the high amount of praise and success the game enjoyed should teach us a couple of things. Starting with how making player-centric games can catapult our products to stardom. Designing from the user out, taking into account how he or she feels when playing our game, is something we need to have hard-coded as a game design principle.

Multiple players, multiple skills, multiple difficulties

Gamers bring their own skillset when they arrive to your game: there are no game virgins (really, there aren’t). They bring tools and resources that they learnt and used on other games, but expect yours to build upon those and provide a new challenge. That’s why each game raises the bar for the next one. And so it comes down to decision time: will you make a complex game that engages a hardcore audience, or come up with a simple challenge that won’t scare away a mainstream user? There’s no right or wrong answer here, but mark my words: you need to answer this before you even make the first level mockup.

As you might have figured from what I said above, I won’t encourage you to try and make a game that everyone can enjoy. Everyone is no one. I, on the other hand, would have you consider these thoughts and eventually decide who are you making your game for. Commit to your gamers, and provide for them a challenge that forces them to learn new tricks, while taking advantage of the baggage they bring. Having enough flexibility to offer an adequate challenge to a wide audience, while not aiming at everyone sounds like the Holy Grail of game programming.

Making your games player-centric also means that you need to avoid thinking of yourself as the target of your games. Why? Because, well, there can only be one of you. Like Highlander, you know. They need to work for someone other than you, else they are just an exercise. Pay extra attention to this, because it’s a very common mistake, and something that could ruin a project, no matter how much work you put in it.

So.. how do we go around building all this into games?

Successfully driving the gamer through a game so-called “learning curve” is key for an enjoyable experience. The tutorial is a widely used resource to ease the user into the game, but truth be told, it’s rarely used. And to be honest, a tutorial is not an elegant solution: in an ideal game, players would learn to play playing. So, is there a way you can work the tutorial seamlessly into the gameplay? If you do, then you are guaranteed to hook the gamer long enough to demonstrate what else is in it for him, if he continues playing.

The popular saying pops to mind here: “Easy to learn, hard to master”. See how this relates to the flow experience? Easy to learn means you can hop right in, there’s no high entry barrier that will result in anxiety. Hard to master means that, as you progress, there are subtleties built into the design that will reward the persistent player with tougher challenges: the game will continue to be fun, because the more he knows about it, the more difficult it gets (and this doesn’t necessarily have to do with levelling up). When Nolan Bushnell came up with Pong, he wasn’t happy with the first result. The position of the ball was too easy to predict, there was no real challenge after the first couple of plays. The game just wasn’t fun. And then it struck him: What if the position and speed of the paddle affect the ball’s trajectory? Wow. That single design decision turned Pong from a fun experiment to a game-changing (pun intended) event in the history of videogames.

How do you evolve with the player, as he gains better understanding of your game’s rules and difficulties? What you presented as a challenge on Level 1 will probably not be so on Level 10. How do you negotiate this skill difference in-game? There are important game design lessons to be learnt here as well, and you need to dig in your game prototype to find out more about it.

Big-brand games have sorted this out in a variety of ways. For instance, for a while now we’ve been seeing multi-layered games: there are several dimensions at which it can be played. The user can sweep through the maps or levels in a linear fashion, or try to unlock all the secrets, or get all the achievements. Doing so takes more time, more energy and probably more skill, but also offers a reward. And so, the idea of challenge is closely tied to the concept of rewards. If the player sorts a challenge successfully, he should get a reward. But as much as I’d like to get into rewards, we are drifting away from our subject (and this will also make an excellent post in the near future!). So, let’s go back to flow, and how it affects us.

There are more elements that we can explore to engage the user, and provide an experience as enjoyable as possible. We can use a powerful story to drive the game, or focus in an exquisite ruleset. We can aim at creating a living, breathing world, or set a linear, breadcrumb path for the main character to follow. On upcoming posts, we’ll continue to explore these options, trying to make more sense of them, and giving you resources that you can use to build better games that genuinely touch your players.

That’s it for now

Rather than entering an academic, high-level theory discussion about the inner workings of the Flow concept, I think it’s an interesting idea to lay out on the table. Game designers can greatly benefit from knowing what works and what doesn’t for their players. Throwing the player into a “flow” state (or whatever you want to call it, that’s alright), where he’s enjoying the process and meeting challenges that are tuned to his skill level should be the aim of every game designer out there (and that includes you!). The only way to get this right is to put the people behind the controls in the center of your design: not necessarily the graphics, or the rules, and certainly not what you think might be right or wrong: you need to go out and ask them directly, have them play your game and spend as much time tweaking as you spend developing. Only then you may end up with a game that has the makings of a classic.

There’s a popular quote from Jorge Luis Borges that goes something like this: “Let others take pride on what they wrote: I’m proud of what I read”. Being a great reader is the seed of a good writer, and being a great gamer is the seed of making great games. So, no matter how many games you make, don’t forget to keep playing!

And remember, this game design lessons series need you! Drop by the forums, comment on the post or give us a shout over email to tell us how you liked it, and what would you like to see featured next.